Take that Trouble Spot Out of the Box

In a perfect world we would all be perfectly prepared to tackle a piece before we ever attempted to learn it. Spoiler alert! The world is rarely perfect and neither are we. Being a musician means you are handed a piece and expected to make it work. Being a teacher means that every student you work with comes with a set of strengths dependent on their background. We all have some things we do better than other things. Bonus: we learn best when we have questions combined with just the right amount of frustration.

I like to customize exercises for pesky technical passages from basic technical elements for myself and my students. Mastered scales and arpeggios mean that we can apply patterns or rhythms to something that is nearly automatic. Taking trouble spots out of the box like this moves the needed skills out of context and allows them to be used in a new way or in many ways. It allows you to focus on and diagnose a single problem without the distraction of interpretation. Here’s the bad news: most of the time a single problem is actually comprised of several elements and the one you think is the worst offender often isn’t.

Here are some examples of troublesome passages and our ‘out of the box’ solutions to strengthen them. Once you start thinking this way, you will amaze yourself with many creative ways to practice those trouble spots and your practice effectiveness with go up a whole lot of notches.

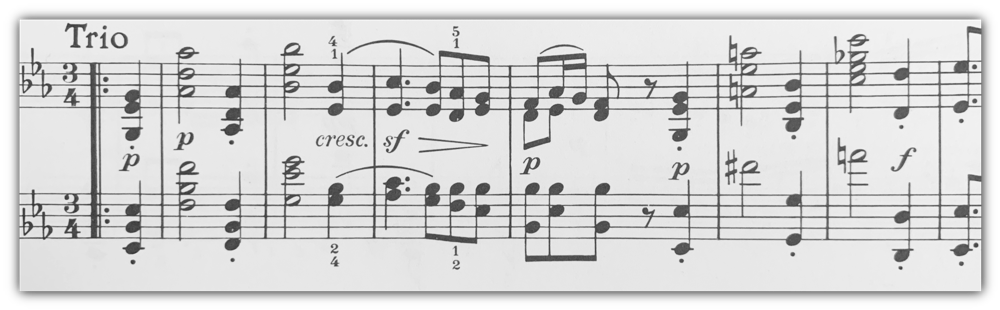

Pesky Arpeggios: Schumann, Davidsbundler, No. 15

When I was learning these wonderful dances years ago, I found that the arpeggios in the 15thdance did not fit my hands well. It didn’t seem like they shouldn’t have been a problem but problem they were. Something about the hand spacing combined with the turn-around made it awkward for me. So, I took the arpeggio pattern out of context, played it in every octave, and applied the pattern to every key and chord quality. It was actually quite fun and of course, sounded very grand.

I did all my arpeggio warm-ups in the pattern for months. It worked. It was a double win because I started to be more aware of my student’s trouble spots and to invent or adapt exercises to fit them too.

Uncooperative Octaves: Mozart: Alla turca (Sonata K331)

This B section is not too difficult when the melody is in single notes. But the octave rendition later in the piece trips up many pianists. We practice it in straight 8ths (rather than “grace notes” and make sure that they are playing in as straight a line as possible as they move from white keys to black. Many people don’t notice that they are moving in and out form the far edges of the white keys. We also practice the thumb alone.

Next we apply the RH broken octave pattern to scales and arpeggios in every key. Then, we add the LH pattern as we play those scales and arpeggios using the tonic, subdominant, and dominant of the key. They say they feel like hotshots at home when they do this.

Cantanaerous Large Chords: Schumann, Jaglied (Waldszenen)

One of my students had unexpected trouble with the large chords in this stirring hunter’s song. I was completely surprised because I had heard them play similar things with no trouble plus they played 4 part hymns at church. When I asked, they said- Well, I actually just play the melody and fill in the other parts as I want to. That explained their awesomeness at harmonizing melodies and creating variations. But, now we needed to solve the current situation for this piece and the future.

So, we practiced all the triads of the key hands together, in octaves. Then, we applied that to every major and minor key. We also did progressions in octaves. Try it sometime. With pedal it sounds like a concerto.

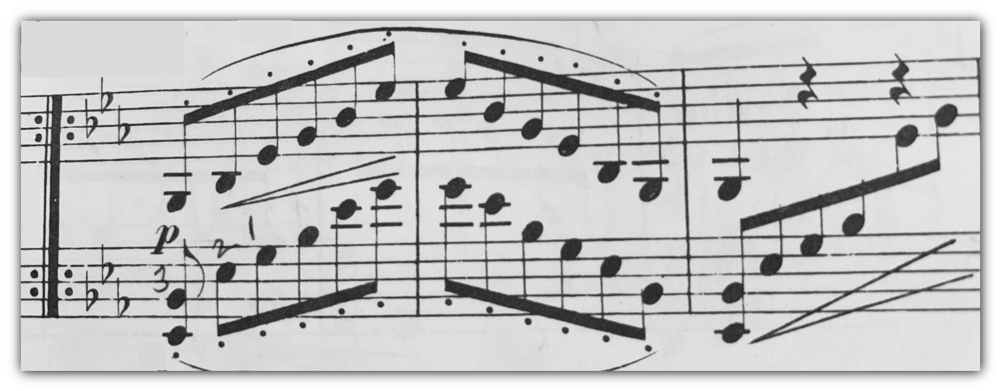

Wayward Leaping Octaves: Beethoven, Menuetto (Sonata Op. 31 No. 3)

The large leaps combined with the octaves in this passage challenge both accuracy and memory. The 4 pairs of chords are made more complicated by the fact that the LH plays octaves in the first two patterns and octaves followed by single notes in the third and fourth. Thank goodness, the pattern just moves up by step, if you take out the octave leaps. This makes for a simplified way to start.

We strengthen the pattern by playing the first individual chord and repeating it 6 times. Then, we do this in every octave. Next, we do the same for the second chord. Third, we practice the first 2 chords in the same way to get the distance secure.

Our next step is to repeat these steps for each pair of chords. Taking the chord pairs out of context reinforces the sounds, handshapes, and distances. Once all four pairs are secure, we use a spinner or flash cards (regular playing cards work wonderfully as number flash cards btw) and practice the pairs in random sequence.