In Your Face Two

Remember the old story about the class of young music students who were told by the teacher that they must all comment after each other’s performances, and, they must always say something good first and then give suggestions for improvement? Tommy had not practiced and struggled through his piece with many do-overs and inaccuracies. Suzy was asked to comment first and she looked down at her feet, up at the ceiling, and hemmed and hawed for some time before she finally told him, “I like your socks.”

Remember the old story about the class of young music students who were told by the teacher that they must all comment after each other’s performances, and, they must always say something good first and then give suggestions for improvement? Tommy had not practiced and struggled through his piece with many do-overs and inaccuracies. Suzy was asked to comment first and she looked down at her feet, up at the ceiling, and hemmed and hawed for some time before she finally told him, “I like your socks.”

Yep, finding the right listeners is important at every level of preparing a piece.

A good listener provides feedback, shares successes and failures, and shines a light on the path forward. This person homes in on your artistic message and helps you to refine it. The right listener thanks you for playing for him or her and tells you things such as, __________ has worked for me, beware of __________, I ran across this problem once and this is how I solved it, what I enjoyed most was __________, or ____________ didn’t work for me—what were you going for there? The right listener adjusts their comments to your level—first tryout in front of an audience to final polishing of a big performance—without being patronizing.

The wrong listener is more concerned with his technique or her interpretation than with yours. The wrong listener may tell you that you need to hear the honest truth (who’s truth???), that you aren’t ready—may never be ready—and you should stick to _________, that you really need to know _________ before you make a complete fool of yourself. The wrong listener fashions him or herself a critic.

From Ann Lamott’s Bird By Bird comes the following description of how she handled a situation where abusive, brutally honest feedback was given by one class member to another:

“…I focused on the fact that the author had tried something so difficult, had taken such a risk. I told him the best possible thing was to shoot high and make mistakes, and that when he was old, or dying, he was almost certainly not going to say, “God! I’m glad I kept shooting so low” …I told the young woman, in front of the class, that it had taken guts to say what she had said. Later she sought me out and asked if I thought she was a monster. I told her I thought she’d been very honest, and this was totally commendable, but that you don’t always have to chop with the sword of truth, You can point with it too.”

When I would get frustrated over picky work and comments, my teacher used to say, “Congratulations, it means you are getting better.” I always appreciated this understanding way to help me strive for the next level. So many students don’t realize that you never really absolutely know a piece—that each work matures and changes throughout your lifetime, alongside yourself.

My students visibly relax when I play examples of a single work recorded multiple times in an artist’s lifetime. It takes enormous pressure off a person to know that you don’t have to get it cosmically right—that there is no absolute set in granite right, just right for you and what you have to say at this particular moment in time. That isn’t to say that you don’t have to be the best you can be at this particular moment, just that you don’t have to be someone else’s best.

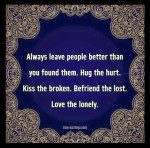

A good listener appreciates who you are right now, period. A good listener understands and expects that you will grow and mature—that life happens and informs your art. A good listener encourages you along in your musical journey. A good listener is trustworthy.

People don’t always know how to give comments appropriately, especially if they have watched shows like American Idol, or Celebrity Apprentice, or one of Gordon Ramsey’s many series. Some who want to be good listeners simply don’t know how to change how they think about themselves and others because they have family members (and sometimes teachers) who run the gamut from not encouraging to destructive.

Ann Lamott (again from Bird by Bird) has the following to say about someone who is negative and destructive about another’s work, “He says how sorry he is that this is how he feels. Well, let me tell you this—I don’t think he is. I think destroying your work gave him real pleasure, pleasure he would never cop to… I think you should get rid of this person immediately, even if you are married to him. No one should talk to you like this.”

We must grow good listeners and to this end I have compiled some ideas which I hope students, parents, teachers, and friends will find helpful. Here are 10 suggestions about being a good, encouraging listener yourself and helping others do the same.

1. Always, always, always say the good stuff first! Try prefacing statements with “I liked” or “I enjoyed.” Be careful with humor. It can be taken badly.

2. Avoid words like good, nice, better. I liken statements which use these words to “It was yellow” or “It was purple.” These words are not specific enough to be helpful. What specifically was good or nice or better? In which part of the piece? Why?

3. If all else fails, speak about the imagery the piece brought to mind.

4. When giving constructive criticism, be sure and give suggestions as to how to accomplish what you are asking for. There is nothing worse than being given an idea without being given the means to put it into play. If someone in the class leaves this part out in their comments, ask class members for suggestions.

5. Always ask the performer if they have questions. Remember the person playing doesn’t experience the piece the same way as a listener does. Something that is obvious to everyone else may no be so to the performer.

6. The teacher should always speak last.

7. If someone in the class is abrupt or undiplomatic try the two word method to restrain them. Everyone must give just two words to describe a performance. Then you can call on certain individuals to elaborate verbally. This is also usually very uncomfortable for the undiplomatic person.

8. Try the two word method combined with written comments or drawn pictures (yes, high school students still love to draw pictures.) Usually, I have found that the undiplomatic don’t have time to write as much as they might say verbally before you call time. Also, most of them tend to do a bit of self editing when writing as opposed to speaking. Again, keep control by limiting time and those you call upon to elaborate verbally.

9. Make and hand out cards or forms for each musical element (note accuracy, rhythmic accuracy, phrasing, technical ease, pedaling, imagery, etc.) Help young listeners along by asking them to focus on listening for just one thing at a time. I assign a different element to each student and rotate them as each student plays.

10. If someone in the studio is completely, uncontrollably inappropriate, simply don’t invite them to studio classes. I have only needed to resort to this one time in over 30 years of teaching. It seems extreme but if you think about it, the undiplomatic person is making life miserable for the others in the class and isn’t learning what you want him or her to from the class situation anyway.

What a great program! We were having coffee at the beach this week and there were a bunch of teachers sitting at the table beside us. One of them said, ” I told her- I have more experience than you but you guys are more intelligent and creative than I ever was.” He was talking about algebra but…

This is such a great post! It reminds me of a theatre program I know that would literally spend the first semester of freshmen year teaching their students how to give constructive criticism and how to receive it.

They told people to give their comments as their own subjective perspective. So for example in music, instead of telling the player “you didn’t play enough dynamics,” you’d say “I couldn’t hear as many dynamics as I think the composer may want.”

Because they were all taught how to give criticism, they were also able to differentiate comments from the outside world that they should take in for themselves or not.

That sounds really neat — possibly even to allow youngsters to witness adult sessions without speaking … and the same for the adults (which might be harder to manage!). To see and hear what the more or less experienced say to each other. And added to that, a session where everyone gets to talk.

Great comments as always. They made the following come to mind:

11. Mix levels in your studio classes. It helps the more experienced to remember where they have been and the less experienced to realize it’s not all about the notes and technique.

… you don’t always have to chop with the sword of truth, You can point with it too.”

Yes! I’ve never understood the way that the words “brutally” and “honest” keep popping up next to one another. I don’t see why people use honesty as an excuse to be jerks. “Brutal” and “honest” have nothing to do with each other. Sometimes I like the word “accurate” better than “honest.” People think “honest” means they get to get away with being creeps.

My students visibly relax when I play examples of a single work recorded multiple times in an artist’s lifetime.

I wish I’d encountered this. This WOULD have relaxed me, instead of the constant message that whatever Horowitz did was RIGHT, period. I keep saying, and it’s true, that I don’t recall my piano teacher badly and that she taught me a lot of great technique, enough to survive after a nearly 20 year hiatus. But if there had been more to the lessons, there might not have BEEN a hiatus. This would have been a great help to me, to know that even the greats are not great because they are machinelike and completely repeatable.

I have so much to say about this, but I think sometimes that being a music teacher must be so hard. You all spend forever trying to get technique into people because let’s face it, music may be natural to the brain but manipulating a complex instrument is an unnatural act that takes years to get good at. And after all that concentration on technique … suddenly you have to almost undo it all by telling the students, “Let’s think about the big picture — where are you headed with this piece, and what do you think is required to get you there? What do you want to SAY through this piece?”

I’m not even sure I would have been able to answer if my old piano teacher had asked me those questions. I was a kid, I associated her with right vs. wrong like I did all teachers, and I was at a point in my life where absolutely everything I achieved was graded. Suddenly being expected to look at things like a 45 year old woman who has decades of experience with more nebulous standards of success would have been impossible.